June 3, 2025

by April MacDonald

On Monday night, true stories of survival and resilience were celebrated at the Nova Scotia Book Awards gala.

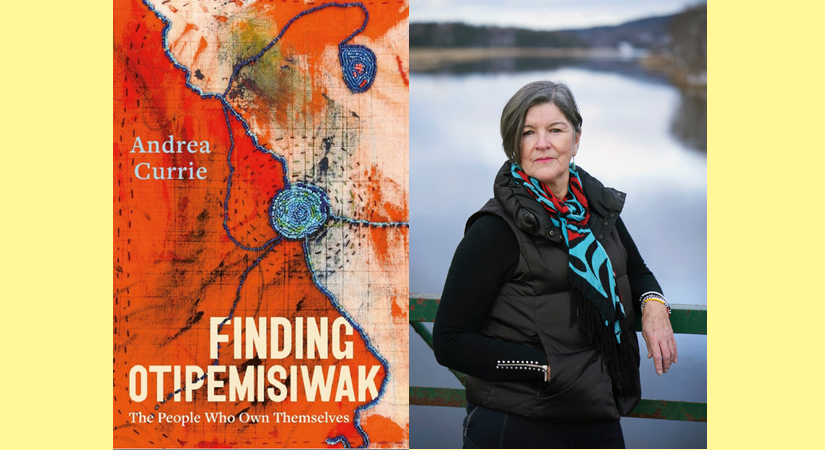

Sixties Scoop survivor Andrea Currie picked up the Evelyn Richardson Non-Fiction Award for the powerful Finding Otipemisiwak: The People Who Own Themselves (Arsenal Pulp Press).

Born into a Métis family and adopted as an infant into a white family, Currie shares her reconnection with her birth family and stolen heritage, and her healing journey to becoming a professional psychotherapist working in Indigenous mental health.

Last summer, Céilidh Gillis-McLaughlin, interviewed author Andrea Currie about her non-fiction book, Finding Otipemisiwak. Otipemisiwak is a Plains Cree word describing the Métis, meaning "the people who own themselves."

Currie explained that the book is a mix of genres; so, it has elements of it that are memoir. “The pieces of it that are memoir, are certain moments in my life that I felt fit into this idea of the conversation about the sixties scoop, because it gives me the opportunity to comment on the bigger picture of what was going on. I use my own experiences as a diving board to get into some of the issues, like cultural loss, Indigenous identity, and blood memory, things like that,” she explained.

“The book also has essays in it where I’m talking about those issues, it also has poetry and a few song lyrics thrown in there too, because I’m also a songwriter,” said Currie.

Currie added that, “it also includes elements of my younger brother’s story. My younger brother in my adopted family was also Métis and his life went very differently than mine and I wanted to honour his story as well,” she added.

She said she wrote the book because she wanted to make a contribution to the conversation about the sixties scoop.

“I’m a sixties scoop survivor myself. I was born in Winnipeg in 1960 and I was adopted right at birth and placed in a white family. So, I lost all connection to my Métis culture and family and history on the land there, which is, of course, the homeland of the Red River Métis Nation.”

She continued, “It’s presented many challenges in my life.” She mentioned how she’s been professionally involved in Indigenous mental health for the last two decades and reconnected with her birth family, and culture, in 1998.

Currie didn’t move back to Manitoba at that time because she had a child here, that’s also why she’s worked in Inverness County for as long as she has.

Being in Inverness County, she discovered ways to make community connections through Indigenous people here, the Mi’kmaq community.

She worked as a psychotherapist as well as a writer, and for many years as a community-based therapist in We’koqma’q First Nation, where she has done a lot of work supporting the healing of residential school survivors. “I came to understand that telling our stories is a part of our healing,” she said.

When asked about when and where she wrote her book, she said that she wrote it over the last four years or so, while living in Port Hood.

The book was mostly written at home but sometimes she would take little writing retreats in a little cabin somewhere.

Currie acknowledged her dear friends in the Shean Poets and Writers Collective, a local writers group who heard earlier drafts of some of the pieces in the book and who gave her really valuable feedback as well as support.

In interview with Gillis-McLaughlin, she closed by saying, that she hopes that as many people as possible will read it.

“I think it will be of interest to people who want to understand more deeply and better what the impact of colonization has been in this country…I think we need to process that understanding [about the impact of colonization] if we’re going to move forward in a different way. So, it’s part of the truth-telling, right? When we talk about truth and reconciliation, this is the truth part. We need people’s stories to illuminate what actually happened because this part of Canada’s history, just like with residential schools, it’s not been told, it’s been hidden. I think people need to understand what was actually going on and how it’s affected a lot of individuals and families and communities and whole nations of Indigenous people.”

“Finding Otipemisiwak weaves together poetry, lyrical prose, fragments, and essays. According to the jury citation, “Finding Otipemisiwak is a survivor’s story celebrating ‘blood memory’ and troubled hearts refilling.”

Other award winners were:

Speaking of blood, OmiSoore H. Dryden took home the George Borden Writing for Change Award for Got Blood To Give: Anti-Black Homophobia in Blood Donation (Fernwood Publishing). A Black queer scholar with an interest in human health, Dryden investigates how racist and homophobic policies became enshrined in Canada’s blood donation system. “Scholarly, well-researched, and exceptionally written, Got Blood to Give engages us in a most meaningful, and timely activism,” said the jury citation.

A third non-fiction award, the Margaret and John Savage First Book Award (Non-Fiction), went to journalist Martin Bauman for Hell of a Ride (Pottersfield Press). A travel memoir of Bauman’s solo bicycle trek across Canada, Hell of a Ride also explores important issues of male depression and abuse.

On the fiction side, Susan LeBlanc brought home the Margaret and John Savage First Book Award (Fiction) for The Nowhere Places (Nimbus Publishing & Vagrant Press). Set in the North End of Halifax in 1979, LeBlanc’s debut was hailed as “engaging and thought-provoking” by the jury.

The Dartmouth Book Award for Fiction was presented to Charlene Carr for We Rip the World Apart (HarperCollins Canada), a multi generational story about motherhood, race, and secrets set against the backdrop of Black Lives Matter protests in Halifax. In accepting the award, Carr said her goal was to have her book pose questions and enable readers to look outside their views and step into another’s shoes. Carr is also nominated for the $30,000 Thomas Raddall Atlantic Fiction Award; she and LeBlanc will read from their novels at the Fiction Fête taking place Wednesday, June 5th, at 7:00 p.m. at the Chester Playhouse.

The Maxine Tynes Nova Scotia Poetry Award went to Cory Lavender for his collection Come One Thing Another (Gaspereau Press). “In this visionary debut, poet Cory Lavender summons, celebrates, and stories the ‘divergent strands’ of his lineage, including his African Nova Scotian ancestry, here lovingly coaxed out of generations of denial,” said the jury.

The festivities culminate in the Atlantic Book Awards gala on Thursday, June 6th, at 7:00 p.m. at Paul O’Regan Hall, Halifax Central Library, hosted by Amy Smith of CBC TV.

Awards to be presented are the Alistair MacLeod Award for Short Fiction, the Ann Connor Brimer Award for Atlantic Canadian Children’s Literature, the APMA Best Atlantic-Published Book Award, the J. M. Abraham Atlantic Poetry Award, the Atlantic Legacy Award, the Readers’ Choice Award, and the Thomas Raddall Atlantic Fiction Award.